How an ERV|HRV Works: The Energy-Saving, Ventilating Box

Tight houses need ventilation – they need polluted indoor air replaced with fresh outdoor air. An energy-recovery ventilator (ERV) or heat-recovery ventilator (HRV) can be a great way to save energy while ventilating your house.

We need fresh air brought into our houses to replace air that’s become polluted with odors, the carbon dioxide we respire and other contaminants like volatile organic compounds that are emitted from the things we bring into our homes. Cooking also introduces particles into the air – from burning cooking oils and fats to burning the gunk built-up on heating elements.

Older homes are|were leaky – they let air through the exterior of the home so ventilation happened whether we wanted it to or not. Leaky homes lose a lot of energy through those leaks so we’re building tighter homes that leak very little. Since that greatly reduces the amount of air flow, we need mechanical (controlled) ventilation for better health and comfort.

How ERVs|HRVs Work

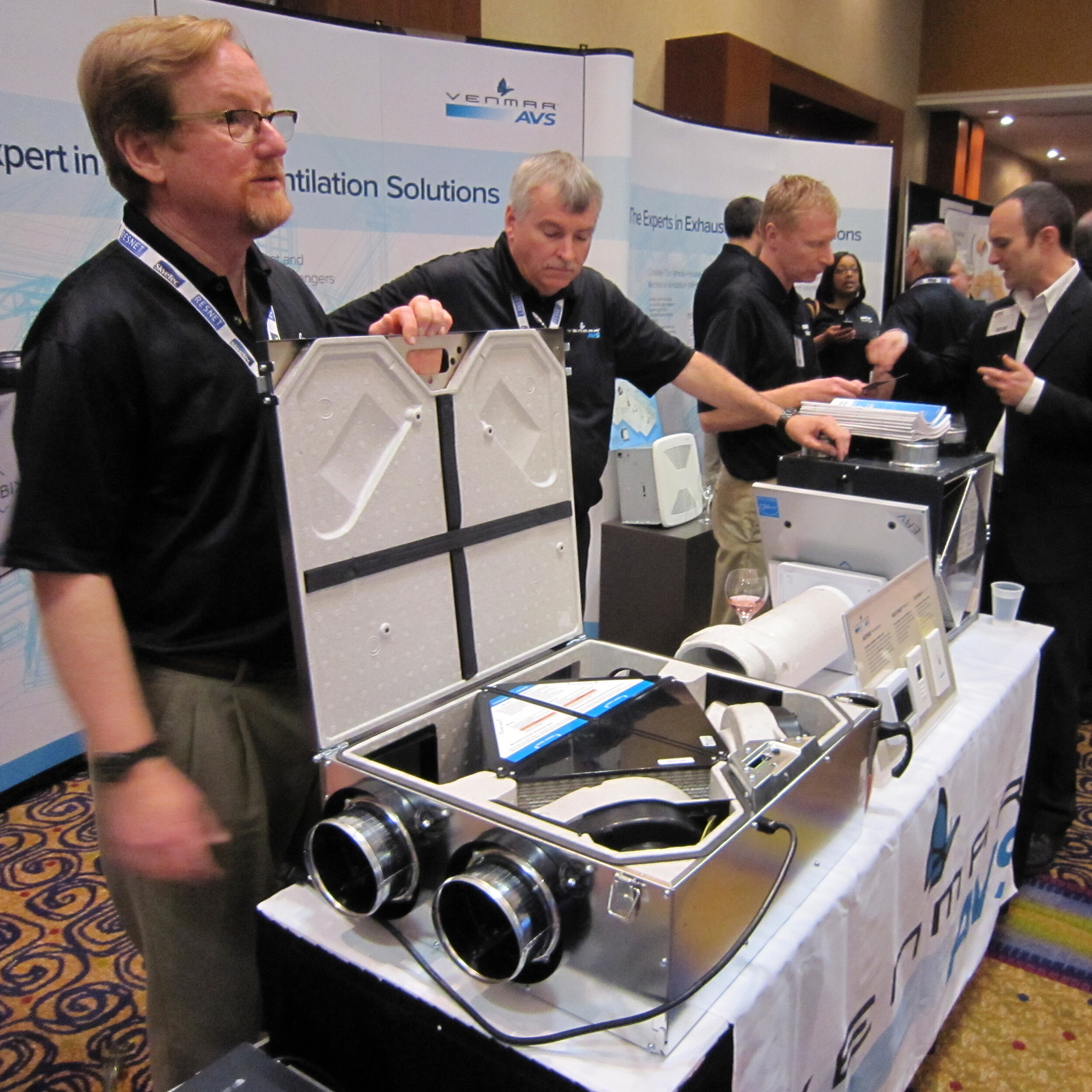

The image below is a heat-recovery ventilator (HRV) at the Navien booth at the International Builders Show. For the purposes of this post, the primary difference between an ERV and HRV is that ERV’s transfer some of the moisture from the incoming air to the exhaust air. This reduces the amount of moisture brought into the house.

An ERV or HRV is typically a simple box with four openings to which we can attach ducts. To understand how they work, it’s helpful to see a recovery ventilator without the cover so you can see how the air flows through the unit. Navien’s diagram over the HRV below makes it easier to figure out.

The tubes on the left side of the unit should be connected to the interior of the house: one stale air exhaust (lower left) and one fresh air intake (upper left). The tubes on the right side of the unit should be connected to the exterior of the house: one stale air exhaust (upper right) and one fresh air intake (lower right). As you can see, the exhaust air crosses the intake air.

The magic of an ERV or HRV is that it exchanges most of the energy in the exhaust air with the incoming air. If you’re heating the air inside your house in the winter, the exhaust air will be hot while the winter air coming in from outside will be cold. That’s why the arrows on the HRV diagram pictured show red (hot) going out and blue (cold) coming in. In the summer, when you’re exhausting cold air and bringing in warm air, the opposite happens.

Efficient units operating in optimal conditions can get the fresh air coming in within a few degrees of the exhaust air going out. Despite the diagram, the air streams never actually come into contact – they don’t mix. The energy is exchanged through a thin material (or membrane) in the core of the unit. The core is the white box in the middle.

The picture above shows an ERV (on the table) built by Venmar, a competitor of Navien. ERV and HRV products are advancing to include some great options. The Venmar unit shown has adjustable fan speeds, dampers to adjust the amount of air flow and built-in testing ports so you don’t even have to open the unit to see if it’s flowing air at the expected rates.

Balanced Ventilation

There are a few ways to provide ventilation in houses. The strength of ERVs and HRVs is that they (should) provide balanced air flow – they bring in as much air as they exhaust. This means they don’t put the house under a negative or positive pressure like some other methods. They can also run independently of the air conditioning system so they can run all the time, be put on a timer or be put on a switch.

A Word of Caution

The choice between an ERV or HRV is an important consideration. It’s not enough to buy one and install it with the expectation that you’ve properly ventilated your home. The choice between and ERV and HRV, the size (air flow) of the unit and whether additional dehumidification is needed are all important concerns that should be included in the overall HVAC design for your home. All components should be coordinated and checked to see that they’re working together as intended once they’re installed.

There’s currently a debate about the proper amount of ventilation in houses – there are competing standards from the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) and the Building Science Corporation (BSC) for calculating the amount of ventilation air required. Bringing humid fresh air into a house, no matter what ventilating standard you’re using, can cause significant moisture problems which result in discomfort, wasted energy and health problems like mold and dust mites.

COMMENTS: We’ve enabled comments for this post to encourage discussion and learn from you. Please review and adhere to the blog comment policy in our Terms of Service if you want your comment to be posted. Requirements include no anonymous posts (first name and last initial is fine). Please include your email address - your email address will not be displayed or added to our email list. All comments are moderated - they will not appear immediately.